I am absolutely blissfully happy living in Lesotho 98% of the time. Not a day has gone by that I have doubted my decision to join Peace Corps, or honestly wished that I was anywhere else in the world. I'm the happiest and most fulfilled I have probably ever been in my life.

That being said, the past 4.5 months (I can't believe it's been that long already!) have not been without their fair share of emotions. And rightfully so. I don't think there is a human on earth who could honestly claim they wouldn't experience a wide-range of emotions at such a jolting life change. Yet I keep most of my blog posts, facebook statuses, letters home, and phone calls positive. Not because I want to deceive, but because 1) I'd rather focus on the positive, 2) there is no point worrying loved ones about things they can't change, and 3) when communication is expensive, I focus on the obvious highlights of my life and work- which all just happen to, of course, underscore how amazing my life in Lesotho and the Basotho people are!

I want this blog, however, to be a record of the honest "good, bad, and occasionally ugly" truth. It's as much for my benefit in writing/processing (and one day remembering) as I hope it is for future PC recruits and their families (for whom PC will be just as much an emotional roller coaster) who will read it. So here we go...

Stage One: Honeymoon Bliss

Once I recovered from jet-lag and the initial shock of waking up under a tin-roof in Africa surrounded by spiders on the walls, I was undeniably, blissfully in love with everything Lesotho. I was in awe at the kindness and love extended to us PC trainees by our new villages and families. I was enthusiastic about learning the language and exploring this new culture. I asked a million questions about everything. My whole world and every minute detail of my daily routine, whether emptying my "pee bucket" or scrubbing clothes by hand, was interesting because it was all "bright n' shiny" new. The sheer act of learning to cook papa (maize meal) and morroho (spinach) with Me' Malehlehonolo (my host mother) was enough to fill me with pride at my accomplishment. I won't deny that the "newness" of everything was overwhelming and emotionally exhausting. But I'd gone from working 50-60 hours a week in an office in the middle of urban-USA... My commute to work used to be 45 minutes of foggy, rush hour traffic, and now it was a sun-rise walk through a rural African village. I felt like my life was finally happening- RIGHT NOW. Every moment of my new reality captivated me. Every cactus flower, dirty child, and flaming red sunset was the most precious thing I'd ever seen. I was in love with Lesotho.

Yet inevitably, we all transitioned out of the "honeymoon" phase eventually. For some it took only two days before a simple comment like, "Ke hloka ho hlatsoa liphahlo haholo kajeno!" (I need to wash a lot of clothes today!) started to look a lot less like an adventure and a lot more like a giant pile of dirty laundry that would require several hours scrubbing, and more than a few miserable trips to the pump. I consider myself lucky. I think I was blindly "in love" with Lesotho for at least my first two months in-country (ie. our PC Pre-Service Training). I somehow during that time turned frustration into fascination, and mundane chores into exciting forays into Basotho culture.

Yet the honeymoon always ends... And end, it definitely did.

Stage Two: Yes, even YOU will get "Culture Shock"

For me, that relatively abrupt halt to “blissfully ignorant love” came as soon as I hugged my PC family goodbye in Hlotse, loaded a half dozen random bags and boxes of carefully selected household items into a van, and drove with a Mosotho stranger (who spoke no English) the 2 hours out to my new village in the nothern-most district of Lesotho. With the move to my new village, Ha Selomo, I slowly started to understand what "culture shock" really means... And it wasn't like anything I had imagined or experienced before.

This is difficult to explain, but its important: The most startling and uncomfortable differences you deal with when you live in a new culture have NOTHING to do with the things you see from the outside. It's not about language, attire, mannerisms, cultural traditions, taboos, rites of passage, or the daily chores which suddenly become necessary to live. I could absolutely care less that I haul every drop of water I use from a pump over 100 yards away, that I live in long skirts because showing my knees would be inappropriate (or at least, attract unwanted attention) in my rural village, that getting to my school means hiking through the fields and a donga (a dried up river bed, that you have to literally climb into and then back up out of), that not a month's gone by when I haven't gotten diarrhea or vomited from water poisoning or some food contamination, or that I find mice in my house and rats in my latrine. To many Americans, these realities sound horrifying, but (and this is the part that's hard to explain) they don't even come close to important when it comes down to what has defined my experience living here. Those chores and occasionally unpleasant aspects of living in Lesotho just simply don't matter. Honestly. They don't even make a dent compared to the things that lie beneath the surface.

"Culture Shock" (a term which I actually abhor, because it illicits some violent image of a disease, that you either catch or don't) is obviously very different for everyone. For me, it was this deep-seeded sense of intense discomfort- As if something, which I couldn't quite place a finger on, didn't quite feel right. It wasn't about the "culture" you read about in a Lonely Planet travel guide or see photographed beautifully on a postcard. For me, it was a sense of not belonging that built up and crept under my skin slowly over time. It came from a million tiny, insignificant social interactions that reminded me there was a social code of some sort, programmed into me so deeply that I'd never truly realized it was there, guiding every human interaction I'd ever had. And then, in the middle of my daily chores or interactions with people, something would make a little chip in it and alert my attention to it's fragility.

It was the unpredictability of other people's actions, such as when, on my first day, strangers kept walking into my house and staring at me without even saying a word (needless to say, I quickly learned to keep my burglar bars locked when my door was open.) Or it was the way that dozens of eyes followed me EVERYWHERE I went because my white skin was like a neon sign that screamed, "Look! Here comes a makhooa!!!" It was differences in privacy and personal space- I still have to actively try to quell my discomfort when strangers hold my hand, when bo-Me nonchalantly touch or gesture at my breasts (breasts, especially between women, are, for the most part, not sexualized) or when a person stands incredibly close to me during a normal conversation. It's the inability to read subtle signals, which especially with men, would normally unconsciously tell me whether I feel someone is a threat or harmless. Here, I suddenly felt like a woman without a "radar" for danger. I've inherently learned to distrust men here, in part, because I'm consistently surprised to find that men I think are simply being kind have ulterior motives.

With "culture shock," its as if I suddenly became aware of all the "taken for granted assumptions" that govern social interactions in any culture, most especially my own. I had suddenly being dropped into a community where, not only was the language different, but everyone around me also had some kind of "rule book," for an unspoken social-language, that I didn't have. It is a completely unique kind of discomfort and personal awareness.

The honest, ugly truth is that my reaction to "cultural shock" (in so far as I can tell from self-reflection) was occasional outbursts of irrational anger at situations that made me feel "out of control." For those of you readers not familiar with my personality, I should probably preface this by stating that I am not effusive with emotions, in the least. My personality is typically very calm, rational, and level-headed. I am slow to anger, and loathe to let others see what I'm feeling. My form of emotional response is more likely passive aggressive, than anything else- Bottle it up, tuck it away, and deal with it later, in private. So needless to say, my sudden propensity to let tiny, insignificant things (such as having someone shout "Makhooa! Makhooa!" from a moving vehicle, or having a group of bo-Me' laugh at me when I tried to communicate with them in Sesotho) drive me to intense and sudden anger, was startling. Something simple would push me over the edge, and it would take a day of fuming and a long, furious blackberry messenger (I am so grateful that I'm able to communicate with my PCV friends in country through texting!) conversation with a sympathetic PCV to help wind me down. I'd HAVE to vent, and I'd have to do it NOW.

It wasn't all the time. I didn't walk around Lesotho in perpetual fits of rage. But it was as if my ability to "bottle up" my emotions had been compromised because the bottle was already full. I had too many emotions- fear, joy, excitement, dread, discomfort, hope- to tuck anything else away to process at a later time. I also think this is why I, an avid reader and writer, did almost NO journaling, blogging, or creative writing during my first 3 months in Lesotho. Processing all those emotions was just too much to ask. For me, Stage 2 was all about survival mode.

So what are my tips for surviving and moving through "culture shock," you may ask?

Step 1: Stay Busy. Seriously... I planted a garden, nested, learned to bake in a dutch oven, studied Sesotho, worked on homemade Christmas presents, and made it my mission to win over the village kids who were terrified of me. Anything to just keep your focus on getting out of bed in the morning, putting on your pants (or in my case, long skirt), and walking outside into the awaiting and inevitable discomfort.

Step 2: Rely on friends who "get it." I could not possibly describe how important my PCV friends in Lesotho have been to me. As an Army Brat, I've watched my father talk about his "battle buddies," and now I (kind of) get it. They are MY "battle buddies" in this experience. Not that joining PC is at all like going to war, but it is uprooting, isolating, uncomfortable, and undeniably terrifying once it settles in. Everyone needs someone who's got their back. :) They had mine, and still do. We're family now, and I know that no matter where we go after Lesotho, this experience will always give us a special bond. Because the unfortunate truth is... As much as we all love, miss, and need our friends and family back home, you just can't "get it" unless you've lived it.

Step 3: Trust that it WILL get better. The good news is, "culture shock" doesn't last forever. It really does get easier. I've only been here going on 5 months and already, when I think about where I was a month ago, I am shocked at how far I've come. The discomfort passes. I still don't like being called “makhooa” or having strange men proposition or stare at me... But as I've gotten used to the villagers, they have also gotten used to me. They learned my name, gave up hope after enough romantic rejections, and realized my white skin really wasn't all that different from theirs. In return, I learned to trust that people weren't laughing AT my Sesotho (but rather, were simply thrilled I was trying), to laugh at things I found akward, and to be bolder with people who made me uncomfortable.

And then, suddenly I woke up one day, and my lovely, little village in the foothills of Lesotho felt like home!

Ha! As if! I wish it was that easy... Welcome to Stage 3!

Stage Three: The super uncomfortable quest for the ever-so-coveted "Cultural Integration"

From the day I and my 29 fellow trainees stepped foot into Lesotho and joined the "Peace Corps Lesotho" team, we've been haunted by a single desire and goal... Cultural Integration. It's probably the single-most important hallmark of a good PC volunteer. It's the key to our personal safety in country, necessary for our success (whether you're a teacher, health worker, or agricultural specialsit), it makes living here a WHOLE lot easier and fun, and it is not as simple as it sounds!

To be honest, I'm not 100% certain, even after 4.5 months in Lesotho, WHAT "cultural integration" really means, or WHEN I can really say that I've achieved it... But gut instinct and two intense months of PC training tells me, I'll know it when I'm there. Maybe?

The gist of it is this... A volunteer who is "well integrated" is embraced by and accepted in his/her community. It's their home. They are well-known, appreciated, liked, and supported. Importantly, they are also safe... Because in a rural village where the law of the land is the Morena (Chief), you need your neighbors, Chief, and host family to protect and stand up for you. When we PCVs first arrive in village, we might as well be infants just learning to walk around our new little worlds. We don't understand the dynamics of our communities, we unknowingly test the boundaries of tolerance and local taboos, we don't know where and who is safe/dangerous, we don't have an "in" to the village news and gossip, and, to add insult to injury, we don't speak the language. We're relatively helpless. We NEED our communities to WANT us there, or we're at the mercy of who knows what.

So long story short, we need to make friends. Now given everything I described in Stage 2, you can understand why this is sometimes a rather discomforting, awkward, and emotionally exhausting endeavor. You think making friends in a new community in America is hard? Try to imagine the stress of doing it in my village where you don't speak the language, and you know that your safety and success as a volunteer depends on it.

There were days that I LITERALLY did not want to leave my house. I dreaded large social gatherings, where everyone would stare, laugh at, and talk about me, but rarely with me (Because? You got it! I still don't speak Sesotho!) Any day when I interacted with anyone for an extended period of time, was a MASSIVE success. Simple interactions with neighbors or the local children seemed to require actual effort… In part, because these interactions were in Sesotho, but also because, for a self-admitted introvert, they don’t always come naturally. I would literally have to force myself to the brink of social discomfort by walking up to a large group of bo-Me to introduce myself outside the village shopong (shop.) Yes, of course, they were so nice and thrilled to speak to me… But while I’m trying to awkwardly start a conversation in Sesotho, they are chattering away at a million miles an hour, and I’m completely lost as to what’s being said about me. It was stressful. I knew people were watching my every move, and I knew I was being discussed and analyzed ALL over the village. I would go to church and have no idea what was going on. I would take my laundry outside to wash, and the bo-Me would stand and gawk. I would start a garden, and have bo-Ntate come up and tell me I was doing it wrong. Everything just seemed a little bit uncomfortable, and opportunities to REALLY interact with a person on a real level seemed few and far between.

Yet, as much as settling into my village was uncomfrotable, walking up to those bo-Me and starting a conversation was absolutely necessary. I had to wake up everyday and consciously decide to leave my house that day, even if I was emotionally exhausted and overwhelmed by what awaited me outside. Because for my village to “get to know me,” I had to BE there. I had to actual go to church by myself for the first time. I had to go and sit by the soccer field to watch a sport I don’t even like. So I did… You just bear the discomfort, and then one day you realize that it doesn’t seem so uncomfortable anymore.

I still remember the day that I first realized that today, leaving my house and interacting with my community, didn’t feel like “work” anymore… It just felt normal. Like I was just going about my life in this community with my new neighbors and friends. I had gone to church that day, and something about the experience (which I have written about in a separate blog post) just felt different from previous outings in my village. It was the first day I really felt like I was succeeding at “integrating.”

And now, to be honest, I don’t think twice about integrating. It’s not work. It just happens naturally, everyday. I go about my life here, and when the opportunity comes to meet new people or explore a neighboring village or caves, I go excitedly and without hesitation because now I have friends, colleagues, and students in village who KNOW me. I enjoy spending time with them. I go out to haul water, and the bo-Me at the pump greet me by name and ask me how the Form C’s did on their Math Exam this week. My house always has children running in and out with homework questions, jump-ropes, and frisbees. And when I return from being away and I see Ha Selomo, nestled in the mountains in the distance, I think “I’m home.”

I wish I could optimistically write that the worst is over, and I’ll never be sad, frustrated, or lonely in Lesotho again! But unfortunately, I can state with absolute certainty that that is not the case. This experience is all about ups and downs… And persevering through them, often in spite of it all. So where am I right now emotionally?….

Stage Four: Learning to LIVE with Reality

I have now been in Lesotho 5 months, living in Ha Selomo for 3 months, and teaching at Linokong High School for just over a month. The major transition is over. There are, fingers crossed, no more life-altering “unknowns” in my immediate future. I love my village and school. I have finally got the hang of my class schedule. I’m starting a “Math and Science Club” at my school, love spending time with my colleagues, and am really getting to know a handful of my students well. I’m happy, content, and settled in… For the most part.

The stage that I (and at least 2-3 of my fellow PCVs) am struggling through now is all about learning to live with my new reality. This is my life now. It is my life EVERY SINGLE DAY for the next TWO YEARS. I will not see my family for at least another year (when they come to visit Africa.) My best friend is getting married in November, and I will not be there to stand by her side when she says her vows. My brother is graduating from University in May, and my sister moves to college in August. My father is retiring from a life-long career in the US. Army. And through it all, I will be here… Waking up under a mosquito net in a tiny rondaval, bathing in a bucket, hauling water, hiking to school, scrubbing clothes, teaching, waiting for taxis in the sun on a rural dirt road, praying to find cheese in town on Saturdays, and looking forward to an occasional visit with PCV friends who live hours away. This is my new reality. And boy is it ever starting to set in. I am at the beginning of “the long haul.”

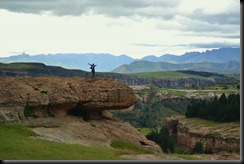

I don’t really know at this point, whether I’m handling this stage with grace or “how” I’ll handle it at all. To be honest, it comes in waves. Yesterday morning, I was incredibly sad and lonely, as I sat in my staffroom surrounded by my colleagues, whom I love but who all speak and joke in Sesotho 90% of the time (thus leaving me out). I am surrounded by people, but lonely. Yet by that very same afternoon, I was hiking across the mountain behind my village with 3 of my students, taking silly photographs, and enjoying some of the most gorgeous mountain views you’ve ever seen. It was exhilarating, and I wouldn’t have traded it for the world.

I’m so blessed to be here… And I know it. But not every moment is bliss and happiness. It’s hard. Really hard. And my emotions about living here change, nearly by the minute. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t feel tested, and simultaneously a little stronger for it. I know that I will be a better person for this experience, and I know that being here is absolutely worth it… Because the moments of self-doubt, insecurity, and discomfort only make reaching the top of that mountain all that more joyful.

With Love from Lesotho- M.E.